Digging Diary 4, 6-11 April 2019: Hunting hieroglyphs in their natural habitat

Week four was quite exciting! We finally started investigating the underground chambers of Meryneith’s tomb, and Luca began to create the 3D model. In the meantime, Nico continued to excavate north of Maya’s tomb and found some very exceptional objects. Stefanie finalised her restauration work in the central magazine with Islam. Beside small finds registration, Daniel and Lara finished the reorganisation of the new storage rooms. Last but not least, team member Huw Twiston Davies arrived and gets the word in the current Digging Diary to introduce himself and his work.

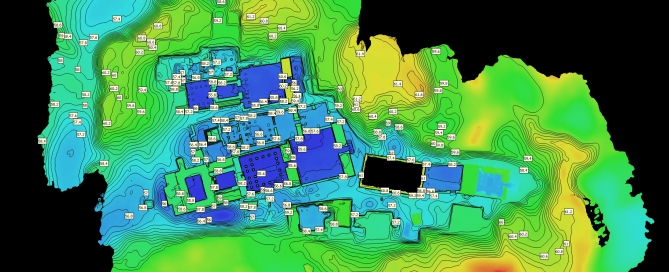

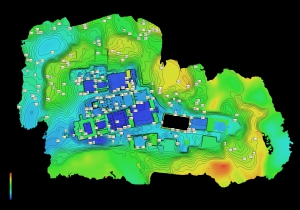

It’s one thing to read about the tombs excavated by various missions in the books they have published. But to really get a sense of the layout of texts in the individual tombs, and the relation of the tombs to each other, you really need to see the site in person. This was my main reason for visiting the site. As part of the research project “The Walking Dead at Saqqara: The Making of a Cultural Geography”, I work alongside dig director Lara Weiss, and team member Nico Staring at the University of Leiden. Our project attempts to understand the ways in which individuals and groups adapted to and shaped their environment at Saqqara over time in relation to their religious beliefs. The aim of the project is to build up a fuller picture of the development of religious beliefs at the site of Saqqara over the course of the New Kingdom by examining the religious practices at the site, the adaptation and editing of religious texts in the different tombs at the site, and the development of the necropolis landscape.

This is quite different from more traditional accounts of Egyptian religion, which often emphasise the strength of tradition, and the continuity of practice across time. While it is true that many religious texts, and the religious practices of priests in the temple may have remained largely unchanged, this does not mean that nothing at all changed in religious practice across thousands of years. Texts could be re-edited, adapted, or reinterpreted, or reused for new purposes. Particular religious rites, and particular areas of a temple, tomb, or necropolis, for doing them could rise and fall in popularity. The apparently “static” Egyptian religion in reality was likely continuously changing.

My main purpose here is to put what I’ve read into context, and see what the necropolis is like in person. The publications of the individual tombs are excellent, but inevitably cannot give much sense of what the tombs are really like; the sense of the size of each tomb, and in particular the layout of the tombs in relation to one another. Published maps give some sense of how the tombs are packed together, but on the site itself, it is easier to see that they are, in some cases, literally on top of one another.

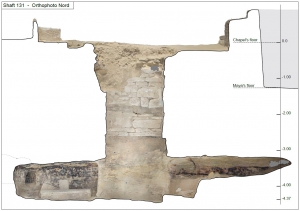

Down in the shaft of Meryneith’s tomb. Photo: Lara Weiss.

It is difficult to get a sense of scale from the books published about the tombs. Some scenes, which are shown in highly detailed drawings in the published volumes, are in reality much smaller. Other scenes are larger, and always, the layout and the connections between the different scenes only becomes really clear when standing in the tomb itself. A large part of my time at the site is taken up with exploring the surviving tombs, and either checking texts against the version published, or noting the physical interrelations between the scenes more clearly. This is achieved by photographing the scenes from a distance, so that their place in the tomb, and sometimes in the necropolis more broadly, can be seen. This helps to build up a sense of how the living might have interacted with the reliefs, and how the Book of the Deadin particular is ‘spread’ across the site as a whole.

Sometimes this involves checking for decoration in the subterranean chambers of the tomb. On Sunday, I joined an expedition into the burial chambers beneath the tomb of Meryneith, which have to be accessed using a rope-ladder, through a deep vertical shaft, which is normally sealed with heavy casing-stones. Unfortunately, this did not produce any new decoration for me, though the human remains stored here from previous dig seasons has provided plenty of work for the mission’s osteologist.

Rope ladder down into the shaft of Meryneith’s tomb. Photo: Lara Weiss.

The most unexpected part of working in the necropolis is the birdsong. A surprising number of birds venture over the escarpment and into the necropolis, presumably to feed on the insects which inhabit the area. In reality, the necropolis is not so far from the cultivation, so it’s not so far for them to fly. We often think of deserts and graveyards as quiet places, but the birdsong is a reminder that ‘quiet’ is a relative term, and in antiquity, it may have been quite different. The sound of funerals in progress, of festival banquets, or the construction of new tombs, all would have made the necropolis quite noisy.

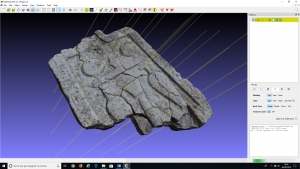

My other chief occupation on-site is to help to read the hieroglyphic and hieratic texts that are excavated, though until the last few days these have been thin on the ground. An offering-table, probably dating to the Late Period and found before I arrived is very difficult to read. In theory, hieroglyphs are quite easy to identify and therefore to read, but after millennia of weather erosion, the forms are often very abraded, and difficult to see on the stone. Sometimes it can be difficult to tell what is dirt, and what is the line of a hieroglyph, or whether a given nick in the stone is part of a sign, or a piece of damage. Sometimes, the eye plays tricks, too, and ‘completes’ a piece of damage, so that you see a hieroglyph where there isn’t one in reality. Reading in these cases often involves the use of a torch, and moving the light repeatedly to try and detect where there are really incisions in the stone. If the text is particularly badly worn, as it is in this case, reconstructing the text can take several attempts, and having several people work on the problem can help to speed up the process of reading.

Daniel and Huw deciphering the inscription on an offering table. Photo: Lara Weiss.

Other inscribed material presents different problems. A fragment of papyrus which was excavated on Monday aroused excitement with the red border visible even when the piece was folded up. This is a fairly common feature in the more elaborate copies of the Book of the Dead, and so might have indicated one of these papyri. In fact, the papyrus is more interesting, but also more puzzling, than this suggested. The remains of the text is very fragmentary. Only two hieroglyphs can be read: one is the number 5, and the other reads ‘i’. The ‘i’ appears at the bottom of the fragment, in what may once have been a single line of text at the bottom of the page, or register. Above it, after a long gap in which everything except the border is missing, appears to be at least one box, with an illustration in it, next to which the number 5 is written. Only a few lines of the illustration remain, so what it depicts is difficult to say.

The format of the papyrus, with a series of boxes containing illustrations, and a line of text boxed in at the bottom, is similar to certain types of papyrus known from the Late Period (c. 664-332 BCE). I thought particularly of the ‘Tanis Geographical Papyrus’ in the British Museum, and our working theory is that the papyrus is some kind of compendium, or “knowledge document” similar to this.

Daniel and Huw in their field office. Photo: Lara Weiss.

But every day on-site is different, and brings new finds and new challenges. Almost anything might emerge from the excavation next. In the meantime, I have many more beautiful reliefs and hieroglyphic texts to examine.

Huw Twiston Davies

If you wish (to continue) to support archaeological research in Saqqara through the Friends of Saqqara Foundation in 2019, we kindly request you to transfer your 2019 donation into bank account number NL18INGB0009562150 of the Friends of Saqqara Foundation, stating “Donation 2019” and your Friends-number.

If you wish (to continue) to support archaeological research in Saqqara through the Friends of Saqqara Foundation in 2019, we kindly request you to transfer your 2019 donation into bank account number NL18INGB0009562150 of the Friends of Saqqara Foundation, stating “Donation 2019” and your Friends-number.