General information on Paser’s tomb

Paser was Overseer of Builders of the Pharaoh and came of a well-known Memphite family. His brother Tjunery (or Tjel), whose tomb was probably situated close by, was Overseer of Works on all the monuments of the King and Chief Lector-priest. In the latter function, Tjunery was responsible for the cult of the deified rulers. This motivated him to represent a proper king list in his tomb, one of the few similar documents from Ancient Egypt. The list was taken from the tomb in the 19th century and is now in the Cairo Museum. The last king mentioned is Ramesses II (1290-1224 B.C.) and this provides a rough date for the two brothers Paser and Tjunery.

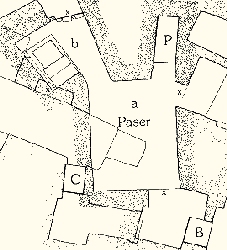

Superstructure of Paser’s tomb

Paser’s mudbrick tomb is a relatively simple affair. It was discovered in 1980, due west of the monument of Horemheb and measures about 7 x 11 m. It consists of a forecourt, screened off from an open courtyard with central burial-shaft, and an offering-chapel flanked by two storerooms. The offering-chapel is the only element to have limestone pavement and revetment. The various wall-panels had fallen down but could be re-assembled by the expedition. The decoration proved to be restricted to the inscribed door-jambs and two pillars, an unfinished stela against the west wall, and a sketch in black paint on the north wall. A large stela now in the British Museum must have stood against the wall between the chapel and the north storeroom. It shows Paser and his brother Tjunery adoring the god Osiris, with other members of the family below.

Substructure of Paser’s tomb

The substructure consists of a shaft of 6.80 m and two chambers. The inner chamber has a sarcophagus-pit for the owner’s burial. Three robber’s break-throughs provide access to adjacent tombs of Late Period date. Two fragmentary limestone shabtis inscribed for Paser demonstrate that the burial was actually carried out. Heaps of pottery found in the south storeroom and on the forecourt and a number of votive stelae attest the performance of funerary rituals for the deceased. The tomb was robbed but does not appear to have been re-used by later generations, although a Coptic rubbish dump gradually filled part of its forecourt.

Most interesting finds from Paser’s tomb

Votive stela

Votive stela

Apart from the stelae which formed an integral element of the wall-decoration, the Saqqara tombs often contained smaller stelae placed against the walls as mementoes of visitors, relatives, or priests. Three such stelas were found on the pavement of Paser’s antechapel. This specimen shows Paser in adoration of Osiris and Isis. Between the deceased and the gods is a lotiform stand with the figures of the four Sons of Horus. The lower register depicts two men and a woman approaching an altar. The first man has the shaven head and leopard skin of a mortuary priest. The inscription in front of him informs us that the stela was ‘dedicated by the offering bearer of Ptah Tjelpare’. Clearly Paser’s relatives had hired a professional priest of the Memphite town-god Ptah to look after the tomb of their ancestor. The other two persons depicted have to remain anonymous for lack of further inscriptions.

Shabti fragments

Shabti fragments

These shabti fragments are the only surviving objects from the tomb of Paser which are inscribed with his name. Both statuettes are carved from a bluish-grey limestone. They represent the tomb-owner in the shape of a mummy. The front is inscribed in one column of incised hieroglyphs mentioning ‘the overseer of builders Paser’. The framed lines around the body contain part of spell 6 from the Book of the Dead, the so-called shabti spell. This summons the shabtis to answer on behalf of the deceased when the latter is called for menial labour in the hereafter. Such work comprised the preparation of agricultural fields, the irrigation of high-lying grounds, and the construction of canals and dikes. Usually the shabtis carry hoes and a sandbag for this purpose.

Wooden mallet

Wooden mallet

This wooden mallet was found against the exterior of the north wall of Paser’s courtyard. It is made of a single block of wood. With its tapering handle and bulbous head it exactly represents the wooden mallets used nowadays in sculpture. This similarity just shows how the ancient Egyptians already managed to find the most practical solution for many implements. Builders’ tools such as these are often found in our excavations. They comprise hammerstones and grinders, plump bobs, pots used to contain paint or plaster, stirrers and spatulas, and of course the artists’ sketches on pieces of limestone and pottery (ostraca). Some of these were discarded when no longer needed, others (such as this mallet) were probably lost or forgotten on the building site.

Paser’s Family Relations

Objects from Paser’s tomb in museum collections

- London, British Museum EA 165: stela of Paser and his brother Tjunery [Paser and Raia, pl. 8]

Bibliography

Final report:

Martin, G.T., et al., The Tomb-chapels of Paser and Ra’ia at Saqqara (London, 1985).

Restoration

The tomb of Paser could already be restored during the season 1981. The whole north-west corner, which was much ruined when found due to the 19th-century removal of the British Museum stela, was rebuilt in modern mudbrick. This reconstruction included the wall separating the central chapel from the north magazine. The various limestone elements of the north and west walls of the central chapel were then re-erected and the floor repaired. A wooden screen was raised in front of the central chapel. Afterwards, the whole tomb has been allowed to be refilled by wind-blown sand, so that now it has again disappeared under the desert surface. No further interventions have been carried out during the 2004-2008 conservation project.